Ask any expedition leader and they’ll tell you the same thing: the Galápagos Islands aren’t a zoo where the animals are kept wild — they’re a stage, and you’re invited to wander through the show. With Ecuadorian National Park rules having tightened in recent years, and a strict naturalist-guide requirement for every landing, access is precious — and wonderfully controlled to keep it that way. So how do you make the most of it? Aim for encounters that happen on the animals’ terms, focus on a few standout species, and savor the moments most visitors only hear about once they’re back on the ship.

1. Snorkel with the World’s Only Sea-Going Lizards

On Fernandina’s Punta Espinoza lava flats, the black rocks are moving. It’s not the sun playing tricks on your eyes, it’s the largest colony of marine iguanas on earth. They bask in massive drifts until midday heats their blood just enough for an underwater lunch run. When the tide is right, they slide into the shallows and graze on green and red algae, sometimes diving 15 feet or more before paddling back to the lava flats to recharge their solar-powered bodies.

Why Espinoza? Unlike sites where human settlement has introduced goats or rats, Fernandina is still predator-free, so iguana numbers are plentiful, and the animals are less shy. Snorkelers routinely share the water with feeding iguanas. Just be sure to bring a wide-angle camera and stay neutrally buoyant; they’ll swim right through your shot if you’re patient. You may also spy a sea turtle or the occasional penguin.

When to go: Activity tends to peak between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. when the sun is high, and the algae buffet is uncovered. Late season El Niño years can hit the lizards hard (low algae means hungry iguanas), but even then, Espinoza remains the best place to see them in action.

Bonus stop — Española’s Christmas iguanas: If your itinerary swings south, Punta Suárez lets you walk through “red and green” marine iguanas — the males blush red during their mating season each December. They’ll be too busy posturing to notice you clicking away with your camera.

Pro tip: Like all cold-blooded animals, iguanas need sunlight, so be sure to give them ample space on the rocks. Throwing shade over a sun-bathing iguana is the reptile equivalent of pulling the plug on a charging phone. They don’t much care for it.

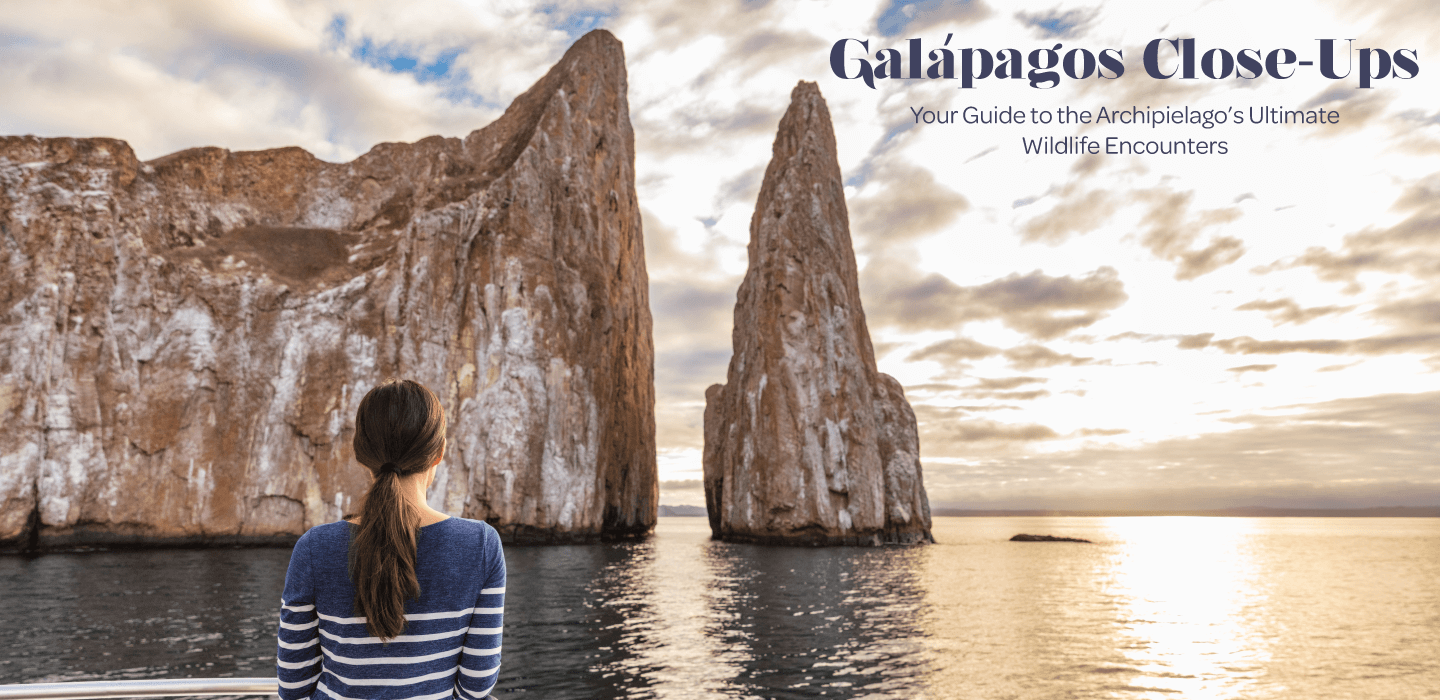

2. Giant Tortoises: The World’s Slowest Time-Travelers

There’s a startling moment on Santa Cruz when your bus grinds to a halt and everyone realizes the boulder in the road is alive. Here, wild giant tortoises roam the highland pastures completely unfazed by humans, plodding between guava groves and rain-fed pools. You can crouch eye-level, your camera lens fogging, while a century-old tortoise sucks down water like a broken fountain. Some of these giant tortoises may be old enough to remember when Charles Darwin first walked the island in the 1800s, as it’s not uncommon for these massive reptiles to live 150 years or more.

Conse in action: While the elder tortoises may have lived at the same time as Abraham Lincoln, just a few islands away, you can meet the babies. San Cristóbal’s Galapaguera de Cerro Colorado (a 30-minute drive from Puerto Baquerizo Moreno) runs a semi-wild breeding center where hatchlings grow in predator-proof corrals until they’re big enough to face the world. Trails wind among pens and into native forest, so you get both close-ups and a sense of how a healthy tortoise landscape looks.

The bigger picture: These sites are part of the long-running Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative, an archipelag-owide effort to rebuild populations wiped out by whalers and invasive livestock. Translocation projects in the last decade have already re-seeded tortoises on islands where they vanished more than a century ago.

Viewing etiquette: It’s advised that you stay at least six feet away, keep voice your low and never stand in a tortoise’s path (no matter how slowly they’re approaching). If they hiss and pull into their shell, you’ve cost them valuable cooling time. Some ranches allow rubber boots for the mud, so use them and spray clean before the next island to avoid seedy hitchhikers.

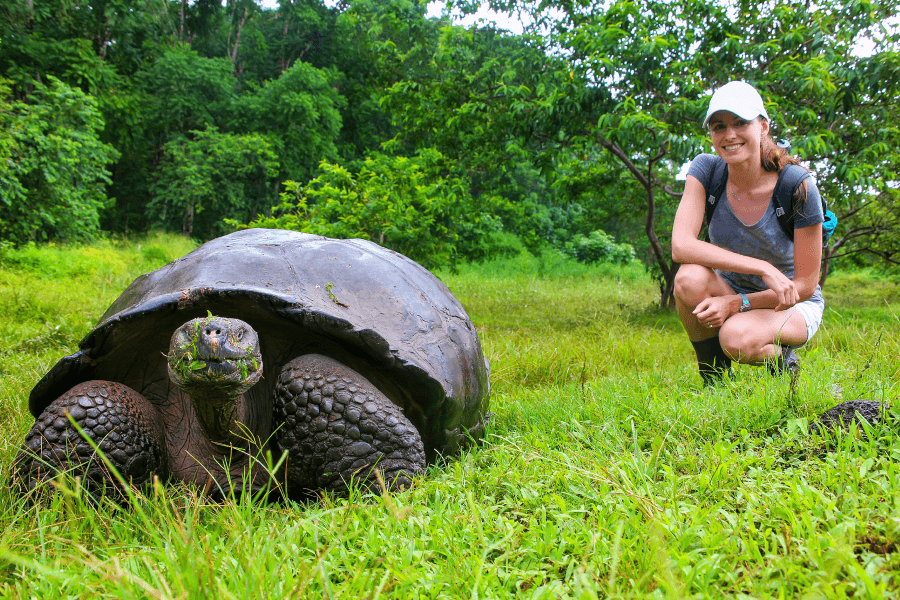

3. Darwin’s Finches: Evolution in Real-Time

They’re tiny, often drab but overwhelmingly important — Darwin’s finches number 17 species (and counting, thanks to ongoing hybridization) and showcase adaptive radiation better than any field-guide diagram ever could.

Prince Philip Steps, Genovesa: If you only land once for finches, make it here. The 81-step climb deposits you in a woodland teeming with birds, including the infamous vampire finch (yes, the one that sips seabird blood). Because the plateau has no large predators, some birds will fly down and casually hop around your boots, pecking for small bugs you might have kicked up while your guide was pointing out their subtle beak differences.

Daphne Major — the evolution classroom: This uninhabited tuff cone near Baltra is where scientists spent decades documenting changes in beak size from one generation to the next. Cruise permits to land are rare, but many itineraries include a circumnavigation and, if conditions allow, a dive or snorkel where the cliff walls ring with finch chatter overhead. Even from the water you’ll see a multitude of these curious little birds.

Why it matters for travelers: Besides bragging rights, watching finches forage teaches you to “read” the Galápagos. Spot a stout-beaked cactus finch and you know opuntia pads (a type of cactus) are nearby; hear the high-pitched buzz of a warbler finch and you’re likely under a canopy of mossy branches alive with insects. Suddenly the landscape is a code you can crack.

Field tips: Carry compact binoculars, wear neutral colors and avoid crunchy snack bags that will rustle and spook the shyer insect-eaters. Early-morning light is best for photos — beaks catch a glint, backgrounds stay soft.

Practicalities for 2025 & Beyond

Since 2024, landing groups are capped at 12 visitors per guide. Cruise ships are typically given time slots for each location, so it’s important to know when your time slot is, where to meet your guide and what to expect on the itinerary.

Gear choices: A 3mm wetsuit is usually enough, but western-island currents can dip below 68 degrees even in the warm season, so layer a 1mm neoprene vest if you chill easily. Sturdy, water-resistant shoes and reef-safe sun protection are also recommended. Some ships will provide you this equipment and even fit you for a wetsuit, but this is a good thing to confirm before you pack.

Leave no trace: Shoe disinfection mats are mandatory between islands; step slowly and let the solution soak. Never sit on lava — microbial life there is slower to recover than the iguanas. Certain types of food may also be prohibited, so be sure to check with your guide.

Photography ethics: Drones are banned. If you must fly, several cruise operators now offer licensed drone pilots who film during landings and share an edited reel so guests can put controllers away and enjoy the moment.

A Living World for Your Living List

The Galápagos is often sold as something you can check off your bucket list, but the magic is in repeat, deeper dives. Plan your route around these three flagship encounters and you’ll come home with stories that go beyond the highlight reel — the marine iguana that swam up to nose your mask, the 440-pound tortoise that owned the trail, the finch that unwittingly made a lightbulb turn on in Darwin’s head while picking seeds from a cactus.

Respect the rules, let the animals set the distance, and you’ll discover what every seasoned guide already knows: on these islands, the coolest encounter is always the next one coming.